Standards are a barrier to innovation?

In a world where we are forced to reducing complex messages to sound bites this is mine on standards in health care IT: “Standards are a barrier to innovation”. Of course this is a gross over simplification and in reality standards have an essential part to play in achieving the full potential of health IT to support the transformation of care. The issue is to understand their role and how to use them to help achieve interoperability.

Robust standards can only be developed when the community in which they are intended to apply has substantial experience and a good understanding of whatever it is they are trying to standardise and this condition, logically, can’t be met in the innovation or early adoption phases of new ways of working.

Standard making is by its nature a consensus based process, or one at least that requires a high degree of accommodation between interested parties, and it is difficult (and rarely desirable) to impose standards where there is not already a broad degree of agreement. The right time to standardise is when there ceases to be an active and informed opposition to the proposed standard. The approach is exemplified with the internet where the core “standards” are called “Request for Comments” (RFC) with a RFC becoming the effective standard when no one feels the need to make further material comment.

Attempts to impose standards on which there is not broad agreement inevitably fail, but worse, slow down the real standards making process.

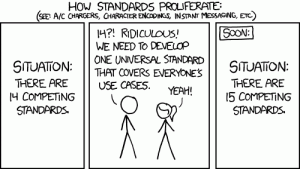

Reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License. Courtesy of xkcd

In recent years NHS work on standards has been something of a curate’s egg with some good work done in areas including pathology results reporting, GP2GP record transfer, Interoperability tool kit and some others. These have all been initiatives emerging out of frontline requirements produced with close cooperation between clinicians and suppliers.

On the other hand grand designs from the top have been less successful, notable, Richard Granger’s exhortation to “ruthless standardisation” in the NPfit. It was never clear if this meant ruthless standardisation on a common system or the ruthless application of standards – It seem to change from the first to the second when the first failed, but didn’t make much progress however defined.

Some of the comments about standards flowing from the NHS Commissioning Board, following the publications of the Information Strategy, have worrying similar features, overestimating the potential impact of central exhortations on standards and underestimating vastly the effort involved in developing and implementing useful standards, particularly at the human and institutional levels (see below).

I’ve been reading “Interop: The Promise and Perils of Highly Interconnected Systems” by John Palfrey and Urs Gasser in which they define interoperability (Interop) at four levels: Technical, Data, Human and Institutional. This is a book worth reading for many reasons, but on standards they make some interesting observations on the relationship between interoperability, competition and innovation; the role of standards and in particular the role of Government and regulators. The case he presents in a complex and I will come back to it in a future blog, but in broad terms he draws a distinction between interoperability and standardisation, argues that the former generally helps retain diversity and promote innovation and competition while excessive standardisation can result in lock-in to sub-optimal solutions. In relation to the role of Government and Regulators Palfrey and Gasser’s analysis suggests that this should be limited to situations where market participant have an incentive to resist interoperability. In the context of the UK Health IT market, I believe that in general vendors increasingly see their best interests lie in promoting interoperability although there are some important areas where some regulatory pressure might be required (e.g. around the oligopoly of GP system suppliers). However, the key area is not with the supplier community but with the NHS itself where Government needs to adjust incentives and apply regulatory pressure to ensure NHS organisations embrace interoperability and ensure the whole system gains the benefit that would flow from it. Currently the incentives (or lack thereof) at the level of individual NHS organisations mitigate against this.

So to summarise: What we need is interoperability at all four levels defined by Palfrey and Gasser. Standards have an important role in achieving interoperability, but need to be applied later rather than earlier in the process if they are not to result in the lock-in of sub-optimal solutions and act as a barrier to innovation. They key to achieving interoperability is in opening up those aspects of systems and data that we need to interoperate, using standards as a trailing edge tool to embed interoperability in “business as usual”. It also important to recognise that the problems with interoperability in the NHS is not primarily at the technical and data layers, but at the human and institutional layers – I’ll come back to this in a later blog.